Information Society

Brian Thompson's assassination illustrates how the seemingly neutral nature of information can obscure its inherent violence. If this story were ever adapted into a television miniseries, the opening scene might pan to an elderly woman sitting alone in her home. We find her staring at an insurance bill she believed her provider would cover, only to discover it wasn’t. Frustrated, she dials the customer service number and is met with a robotic voice listing an array of options. As she struggles to navigate the menu, her frustration grows, her blood pressure spikes, and she collapses from a fatal heart attack. The camera lingers as she lies on the floor, weakly calling for help, while the machine coldly responds, 'I’m sorry, I didn’t get that.'

The example of machinic customer service provides an illustration of how information societies reduce human complexity to numerical and categorical data. This abstraction makes the world more manageable—and profitable—for those in power, but it often comes at great cost to those on the receiving end. With over 52 million customers, UnitedHealthcare, a publicly traded corporation, likely saved millions by adopting practices that minimized the human element in customer interactions.

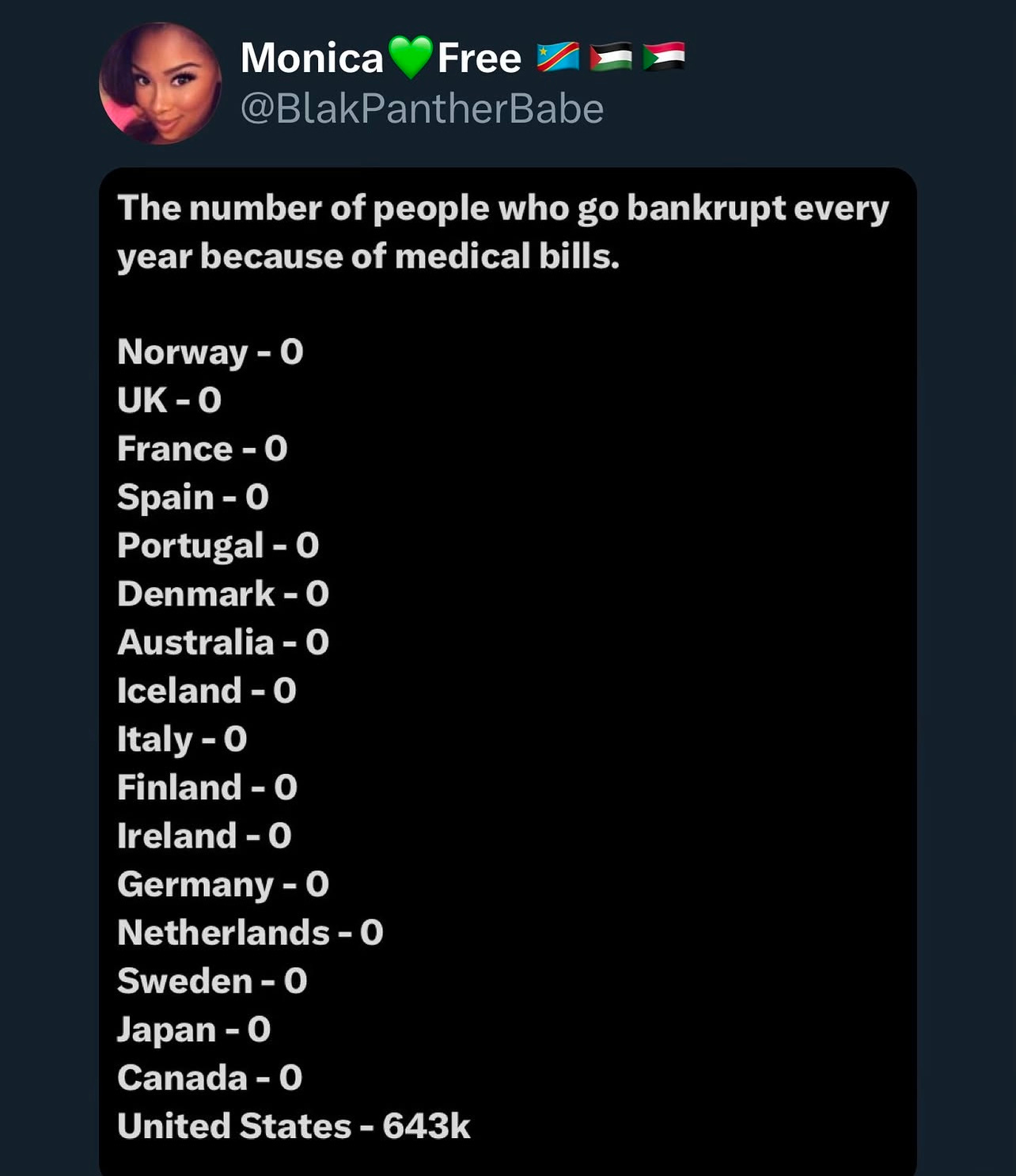

To emphasize this point further, consider these additional examples where information reduces the richness of reality to data points, which are then used to make decisions that disregard human complexity.

Credit-Based Insurance Premiums: Insurers rely on credit scores and other seemingly unrelated metrics to determine rates, reducing individuals to abstract financial profiles while disregarding the complexities of their current circumstances and lives.

Learning Analytics: Educational software compiles performance data to categorize students by proficiency, ignoring the nuanced socio-emotional factors that shape learning experiences and outcomes.

Performance Metrics: Workers are evaluated through rigid KPIs, distilling their value to quantifiable outputs and erasing intangible contributions like fostering team cohesion or enhancing workplace morale.

Risk Assessment Tools: Algorithms in the justice system assign "risk scores" to guide bail and sentencing decisions, flattening the intricacies of individual cases into reductive calculations.

Credit Scoring: Credit agencies distill financial reliability into a single numerical score, often erasing the context of personal challenges like medical debt or temporary financial hardship.

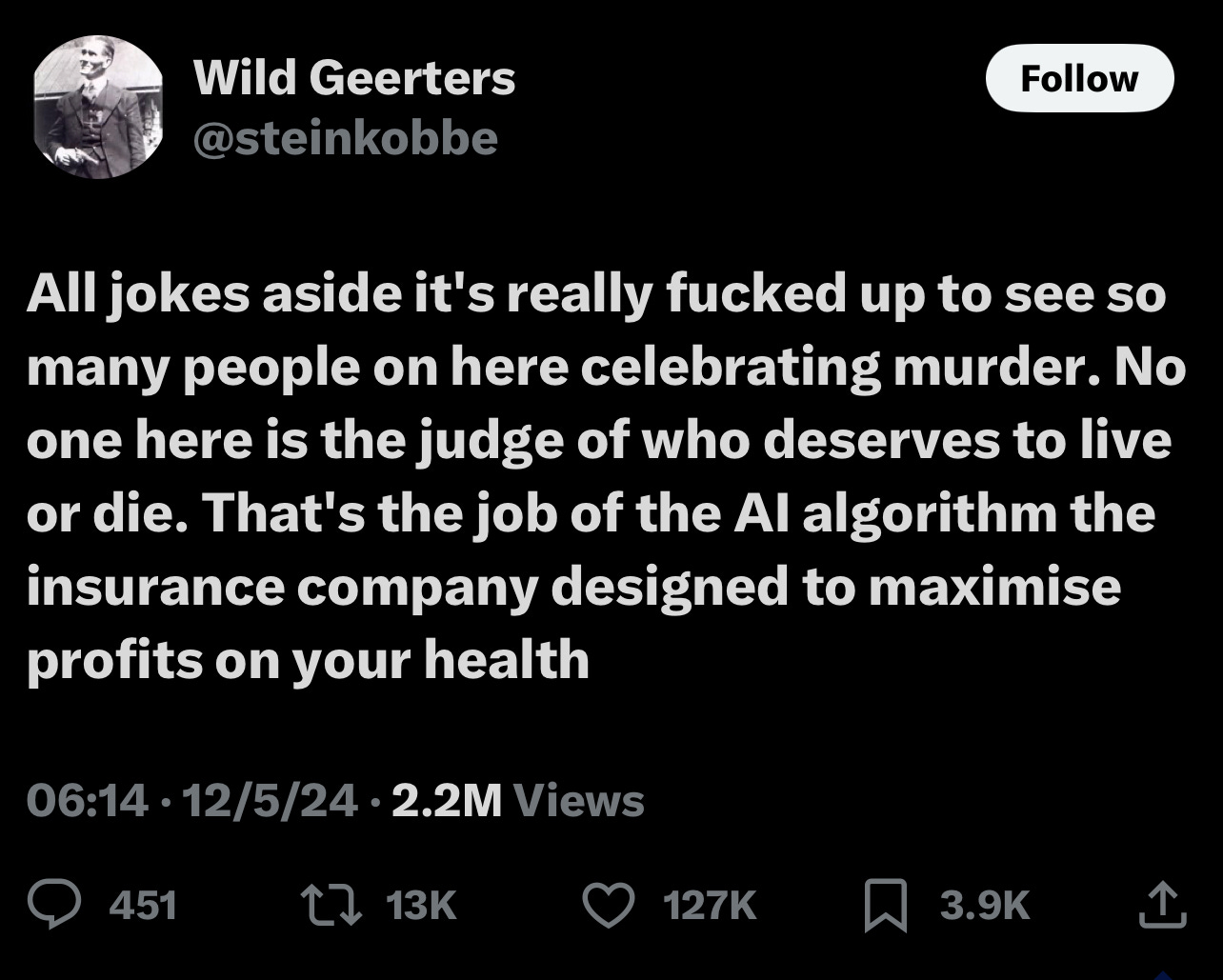

In each example, the reduction of life to information for algorithmic control not only streamlines systems but also fosters a sense of injustice and frustration among millions of people.

Pubic Information

With the digitization of society, our lives are continually transformed and reduced to information that is often made publicly available. A father is reduced to a job title, a potential partner is excluded by settings on a dating app, holidays are reduced to Facetiming our families.

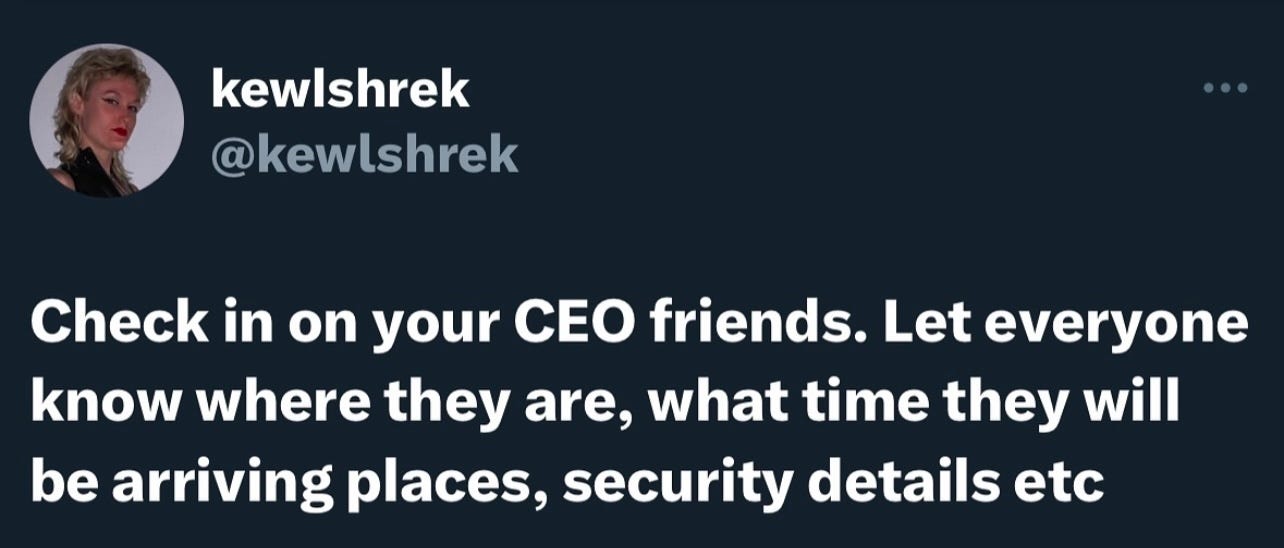

Brian Thompson’s life tragically illustrates this. As a public figure, his whereabouts were public information—a risk he knowingly accepted, which ultimately led to his death. In an information-driven society, this loss of privacy and exposure to danger is not a choice but a necessity imposed by the system. As information societies capture more and more data, they foster an environment of distrust, paranoia, and control, leading to a divided society.

Civil War

The simultaneous collection of data and reduction of life to algorithms create a paranoid and vindictive populace. This reality necessitates mass surveillance programs and drives the push for censorship.

In this way, the information society becomes defined by a silent civil war. This is made most clear by the recent assassination of Brian Thompson and the millions of people on social media celebrating his death.

As governments expand their surveillance programs and corporations collect as much data as possible, this dynamic fuels a reaction that leads to a culture of evasion – driving the adoption of tools like Signal, DuckDuckGo, Tor, VPNs, Faraday bags, cryptocurrencies, Web3, Visa gift cards, non-computerized cars, encryption technology, burners, and masks.

But while the media reduces this war to its content, the war is also able to be understood by the form of each side’s attack which reveals their respective aesthetic.

The Aesthetics of War

By the evening of Brian Thompson’s murder, news broke that the bullet casings found at the crime scene were inscribed with the words deny, defend, and depose—a reference to the strategy of delay, deny, defend. This strategy, as described in a book on the subject, outlines how insurance companies boost profits by “delaying payment of claims, denying valid claims in whole or in part, and defending their actions by forcing claimants into litigation."

In a dark form of parody, the assassin’s appropriation of the insurance industry’s code—a logic that transformed the sector into a leviathan, reducing humans to mere data points—became the instrument of Brian Thompson’s murder. This deeply symbolic act seems intended as a message to the insurance industry, demanding a reckoning with its exploitative approach to healthcare. The assassination of Brian Thompson wasn’t solely about his death; after all, he could easily be replaced by another version of himself. Instead, his assassination was crafted to transcend mere information, resembling something closer to art.

Conclusion

Imagining a future where Brian Thompson’s assassination is turned into a miniseries, I realized that the security cameras that captured the event and the dissemination of the footage by the media have already produced the show. As our information society continues to expand, the silent civil war that Brian Thompson’s death revealed will likely continue to take the form of each side’s respective aesthetic.